Winter fishing on the Missouri River means that you will most likely be doing some nymph fishing. The water is cold and the fish can be lethargic. The most effective method usually involves putting a nymph right in their face. A pink one.

Nymphing is an effective and popular method all year long below Holter Dam. But summer and winter techniques do differ. To be the most effective you need to change it up a little during the colder months.

Where?

You’re best bet is to fish the slowest inside water that you can find. Depths of 3-6 feet deep are the best spots. I like to fish over a silty bottom. It signifies the slow inside drop off, which is where finer sediments get deposited. Silt bottoms also harbor massive amounts of midge larva and pupa, as well as scuds, sow bugs and other food sources that trout key on during winter months.

You need to avoid faster currents, and I avoid the “deep” or “hard” rocky bank, whether I’m wading or fishing from the boat. While there certainly are some big deep seams on these deep banks that harbor lots of fish, in general I prefer the “beach” side of the river.

When?

Days are short this time of year, so you’ll likely be fishing from 9 or 10 am until 5-5:30pm. You’ll often find better action in the afternoons as the water warms, even if only a degree (or less). Midge hatches become regular at the end of the day, and fish move into shallower water and nearer to the surface. In the right weather you’ll even find them rising.

If I only have a few hours, I prefer the afternoon.

How?

The post is about nymphing, so that’s how. While we rig for nymphing much as we do during the summer, how we fish it can be a little different.

Water temperature is a huge factor on our fishery. Few people really realize how cold the Missouri River gets in the winter. Temps typically range from 32.5 degrees to 36 degrees. Think about that. The water temperature is often just over freezing. As you may remember from 5th grade, fish are cold blooded animals. Is it any wonder that the trout aren’t crawling all over themselves to get to your fly? They have to power up just to open their mouth.

So, as the trout become less active, they move to that slow, relatively deep inside water. They don’t want to fight the current, and as their metabolism slows they feed less.

We know where they are and why, so how do we attack those spots?

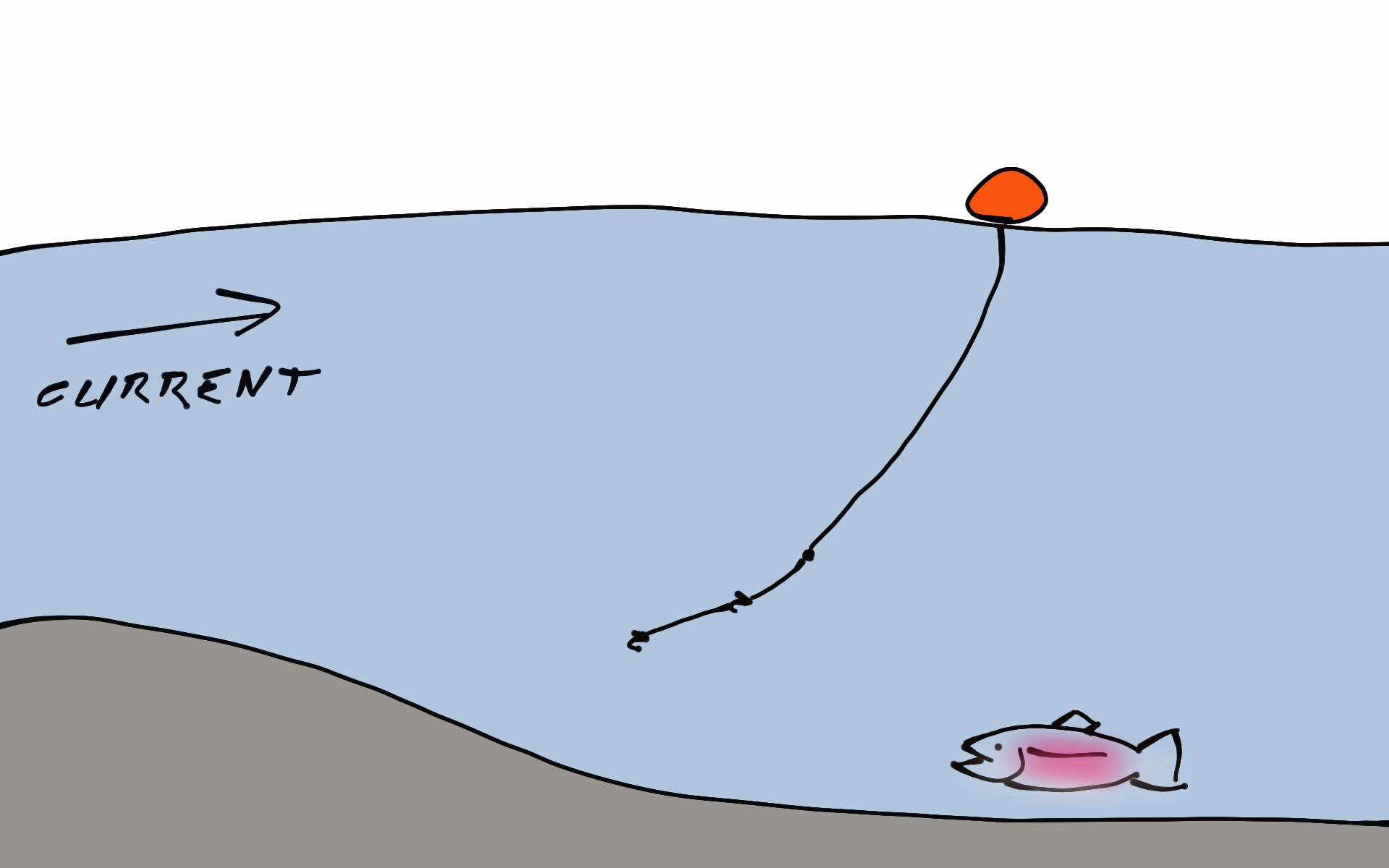

Use weight

The current is slow and the takes are light, so you need to make sure you have a direct connection from your fly to indicator. The use of very small split shot – or none at all – can keep your fly from quickly getting down and allow the current to affect your leader. I typically fish shorter than the bottom depth, but a little heavier than I would in the summer.I want my leader to be as tight as possible so I can detect the lightest takes.

I have had extremely competent fly fishing friends come to the Missouri from other warmer, winter fisheries, and get skunked simply because they are using micro shot, or relying on a bead head nymph to get down to the fish. Once they put a B or BB shot on, they are into the fish. That simple. They simply weren’t getting or seeing any takes.

Set it on Nothing!

Often, visiting anglers don’t realize how delicate the take will be during the winter, especially if they have fished the Missouri during the summer when the fish pull the rod from your hand on the take. It’s not difficult to spend half (or all) of the day ignoring subtle takes before you finally realize that you aren’t catching fish because you’re not following the #1 rule of nymphing. Set is on everything!

In the winter, we also set it on nothing, meaning that sometimes you just sense something funny is going on with your bobber. Or maybe your instincts tell you that your fly is in the zone. Whatever the reason, it’s hard to set it too often in the winter.

Lead it…

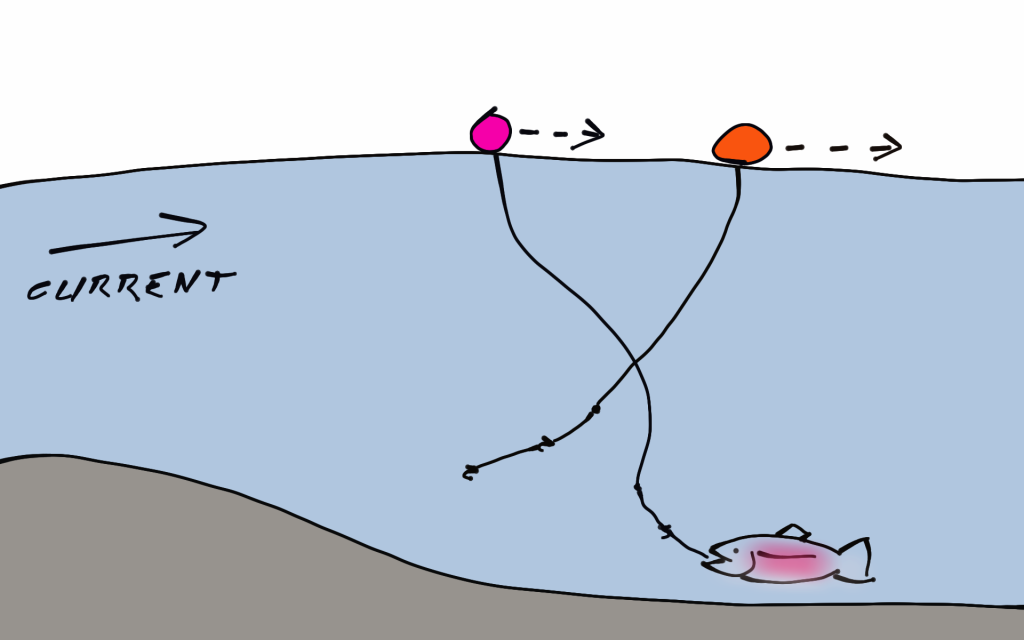

Leading your rig means you need to keep your bobber ahead of your fly. Say What?! Yes, keep your bobber ahead of your fly. You heard me correct. And here’s why…

Trout grab things and spit them out all the time. They can inhale and eject your BH nymph in less than a second. I’ve always felt that it’s not really “the eat” that triggers your indicator, but the movement the fish makes when he turns to grab your fly and returns to his holding lie. This may only be a few inches, but it’s enough to make your bobber move enough to be an obvious take.

During summer months, trout move inches – or even feet – to grab a dead drifted nymph. Flows are often higher, meaning faster, and as the water warms the fish move to faster water to find food and oxygen. This is why we constantly mend upstream during the summer months. We want to slow that fly down, and while we always miss some takes, we get enough of them to keep us happy.

In the winter, fish won’t move much while feeding. They spend much of their time grabbing what is right in front of their face. Combine this factor with the very slow currents fish hold in and it’s doubtful that you’ll even identify many of the takes you get if you have any slack in your line. If you’re constantly mending your line upstream, you’re constantly throwing slack into your system.

By keeping you indicator in front – or downstream – you stand a much better chance of seeing those nearly imperceptible grabs. If your line is tight (remember the weight), and your indicator is leading it, you should be right on the edge of dragging your fly. It should move the instant it stops.

Technically this is pretty easy. You need only fight the muscle memory in your arm that want’s to mend every 5 seconds. You rarely need to actually mend it downstream (if you’re casting upstream).

I also feel that in the “almost dead” water we fish during the winter months, a little movement in your fly may actually be a good thing, and differentiate your fly from all of the stagnant pieces of debris in the water. And remember, we’re fishing water that holds lots of midges, scuds and sow bugs, and these critters swim.

While this is counterintuitive for most nymphers and is not what you were taught, it can dramatically improve your odds of hooking fish in cold water. If you use this combination during the arctic season on the Missouri River, you should have some success in even the coldest conditions.

Nice. Winter nymphing has made me a better nypmher overall. You all have taught me some good stuff on here.

John

Thanks for an excellent job of describing this subtle technique. You have taught me how to adjust for the slow and cold.

Thank you, professor. Always appreciate your willingness to share your knowledge. Hope to put this info to use soon.

Really nice! Appreciated the time involved to put this together. Never commented before on Mark’s blogs……no offense to him!

Great info. Thanks. I’ve been working on this winter nymphing with good success. Looking forward to more.

Informative. Very! You folks are the best educators on the Missouri River.